Little has ever stood between Chelsea owner Roman Abramovich and realising his ambitions for the club.

But plans for a £1bn new stadium are being held up by one family over their right to light – and the lack of it shining into their home when the new Stamford Bridge is built.

The Crosthwaites have lived in their west London cottage for 50 years and it is so close to the Premier League club’s ground that you could almost kick a football from their doorstep onto the pitch.

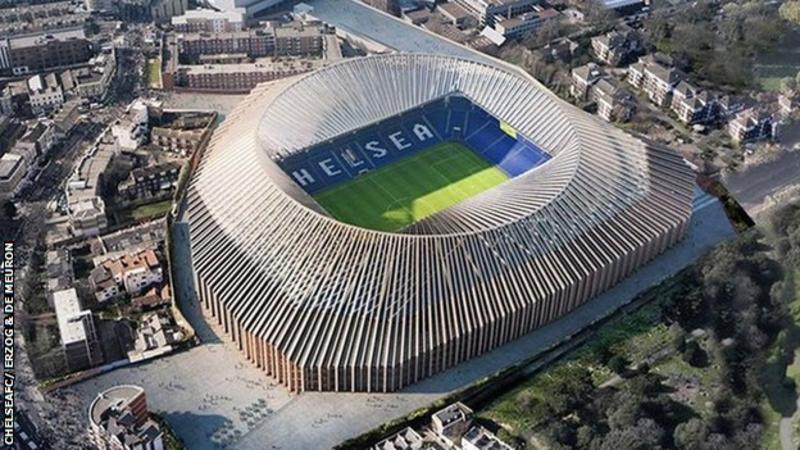

The family – made up of parents Lucinda and Nicolas, plus children Louis and Rose – took out an injunction in May over their belief the towering new 60,000-capacity stadium will cast a permanent shadow over parts of their home.

The new stadium was granted planning permission one year ago and has been signed off by the Mayor of London, but Chelsea have called on the local council to intervene and take advantage of planning laws to stop the injunction effectively ending the planned development.

Hammersmith and Fulham councillors are meeting on Monday to decide what happens next.

Billionaire Abramovich is a man who usually gets what he wants, but the dispute has already put the brakes on the project’s investment and there is a risk that Europe’s most expensive stadium may not even get built.

The club have told the local council that work cannot go ahead while there remains a risk the injunction could successfully stop the development. And the council says if it does not act to help Chelsea the “development would not proceed as proposed”.

What’s the family’s argument?

The Crosthwaites own a large house in an expensive part of west London – a three-bedroom property on the same street sold for £1.18m last year.

Chelsea’s offer of legal advice worth £50,000, and further compensation understood to be in the region of a six-figure sum could not persuade them to waive their ‘right to light’ in their home.

Daughter Rose says their home is the nearest property to the new stadium. And even though it’s on the other side of a railway from Stamford Bridge – and in a different borough – she says that “sunlight and daylight will be seriously affected”.

“It is deemed as having an unacceptable and harmful impact by the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea,” she added in a recent letter as part of the case.

The family have said via their lawyers they are not opposed to the redevelopment of the stadium, but have suggested the east stand in question could be “cut-back or re-designed so as not to cause interference”.

And they have highlighted a “disproportionate amount of hospitality seating” which takes up more space than normal seating.

They say there will be almost 17,000 hospitality seats, 28% of the total, and compare that to Arsenal’s Emirates Stadium where hospitality comprises 16% of the capacity.

The family also believe Chelsea’s attempt to effectively sidestep the injunction with the help of Hammersmith and Fulham council is not in the public interest and possibly illegal.

Their house sits in the neighbouring Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, which they say has been firmly opposed to the development.

How have Chelsea responded?

Premier League champions Chelsea have outlined that the planning and development of their new stadium has been above board on every aspect.

A public consultation of 13,000 local residents earned 97.5% support, and they have paid compensation to other homeowners who have been affected by losing their ‘right to light’.

Chelsea also claim that the new stadium will “further enhance the economic, cultural and social services they provide”, including £6m worth of educational programmes, a £7m improvement to local infrastructure and an additional £16.3m spent in local businesses as 2.4 million people visit the area annually.

That forms the key argument in the part of the law being disputed – section 203 of the Housing and Planning Act 2016.

Chelsea say the land can be compulsorily acquired by the council – and override the injunction – if Hammersmith and Fulham think it would contribute to the economic, environmental or social wellbeing of the area.

The club also says it will lease the land off the council and cover any liabilities or costs.

The family’s lawyers say the council can purchase land “which they require” but ask whether it is “convenient” rather than “indispensable”.

Which way is the council heading?

Hammersmith and Fulham council accepts that acquiring the land should only be done where necessary to allow beneficial regeneration to take place and be sure that it justifies interfering with the human rights of those affected.

A report for councillors, drawn up by head of planning and regeneration John Finlayson and to be discussed on Monday, recommends that the council buys the land (owned by Chelsea and Network Rail) and leases it back to the club so that development can go ahead.

As it stands, the club “will not be able to implement the development or secure any necessary development financing whilst there remains a risk that the existing injunctive proceedings might succeed”, the report warns.

Finlayson’s report adds: “There is a compelling case in the public interest for the council to acquire the land for planning purposes and enable the development to proceed and the public benefits to be realised.”

Without the council exercising its statutory powers, though, the “development would not proceed as proposed” it warns.

It is understood that should the council decide to pursue the purchase, the Crosthwaite family will seek further legal advice – so the case may yet still run.

Chelsea’s battle for a new home

Abramovich has wanted to increase Chelsea’s stadium capacity for several years but was thwarted in his previous attempts to buy Battersea Power Station, ultimately losing out to property developers.

If successful, the Blues would not be able to move until their new home until the 2024-25 season, yet it would at last put them in line with their main London rivals.

Eleven years ago, Arsenal built the 60,000-seat Emirates Stadium, in 2016 West Ham moved to the 57,000-capacity Olympic Stadium, and Tottenham are redeveloping their White Hart Lane ground at the moment.

The 41,000-capacity Stamford Bridge is the seventh biggest stadium used by a Premier League team, well behind Manchester United’s 75,500-seater Old Trafford.

Chelsea are yet to find a temporary home for the four years it might take to build the new stadium, but Wembley Stadium is being considered as a possible option.

–

Source: BBC