Out of the 13,908 prisoner population in 2013, 45.13% were youthful (18-35yrs) according the 2013 annual report by Ghana Prisons Service. In terms of their educational background, JHS students constituted 47% (highest) while SHS was 15.3 % (3rd highest) with offences such as stealing (40.8%) and robbery (8%).

The problem of youth unemployment is not just a central policy issue. It is a national security threat.

Ghana Statistical Service reports youth unemployment to be 5.5% (see GLSS 6, p. 57). Some analysts, including Dr. Baah Boateng of Africa Centre for Economic Transformation (ACET) have emphasized the need to focus on ‘joblessness’ as opposed to unemployment, which is a more accurate measure of economic well-being per capita. Rural Heights Foundation agrees and takes it even further.

Metrics such as the time-related under-employment are also essential in understanding the bigger picture as far as youth joblessness is concerned.

Persons are who are employed but engaged in less than 35 hours of work per week are considered under-employed.

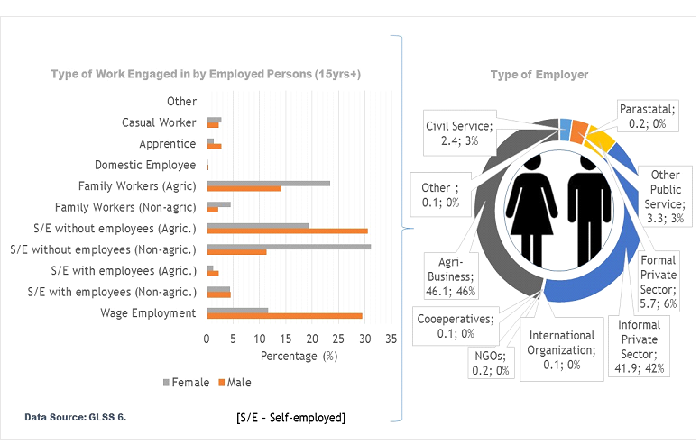

This measure serves as proxy indicator of productivity and labor factor engagement. In analyzing joblessness therefore, it is imperative to take cognizance of not just unemployment, but also under-employment (33.3%) and all category of persons who are employed in non-paying work (family business: 22.3%).

This will help shape a more comprehensive policy response to the issue of joblessness in the Ghanaian economy.

There may also be a need to disaggregate data on the basis of gender, age and locality as stark differences exist between employment for men and women within different age brackets in urban and rural Ghana.

The more pressing questions however are these – what is causing the joblessness? What are the policy options? How do we align job creation with a broader and integrated economic development strategy?

What is causing joblessness?

Recent economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa has been driven largely by natural resource boom such as oil.

Unfortunately new revenue streams have not been matched by fiscal prudence leading to waste, graft and rising debt/GDP ratio. Ghana’s public sector employs about 5.9% of the economically active population whilst the private (formal) sector takes 5.7%.

A volatile commodities market therefore, makes government revenue, and by extension labor employment, vulnerable.

Though the whole private sector (including informal sector: 41.9%; NGO sector: 0.2%; Agri-Business: 46.1%) employs more labor than the public sector, the harsh business operating environment effectively limits output and employment growth. Average lending rate for April 2016 was 32.1% (April 2015: 29%) while inflation in June 2016 reached 18.4% (June 2015: 17.1%). Though volatility on the Interbank forex market has eased for H1 2016, the underlying pressures still exist.

The combined effect of all these is that Ghana’s private sector have become less competitive as reflected in World Bank’s Doing Business Report.

Out of 189 global economies surveyed, Ghana ranked 70th in 2015 compared to 67th in 2014 and 62nd in 2013.

The third factor driving joblessness is bad education. Joblessness is partly the legacy of a bad educational system.

Against this backdrop, the policy to convert Polytechnics into technical universities may have a positive impact, only if skill development is aligned with the World Economic Forum’s sixteen prescribed essential skills for the 21st century; complex problem-solving & decision-making, collaboration, creativity and leadership, to name a few.

The prospect of reforms assumes however, that there is adequate funding, strong faculty and relevant facilities available to implement the program.

Policy Design – What’s the best approach?

Given the problem context, policy design must ensure a sound program logic where assumptions, objectives and outcomes for all sectors are integrated. The following are critical success factors:

1.Employment programs must be private-sector driven. The ills of state interventions are well documented. Markets, when properly regulated, are found to be more efficient in allocating resources than the State.

2.Must align growth objectives with agriculture and agro-processing in order to improve productivity of farm and non-farm enterprises.

3.Must not be burdensome on government budget. The lessons of IMF’s austere fiscal program must not be lost on future governments and policy makers.

4.Must ensure integration with the capital market especially the Ghana Alternative Exchange (GAX) which provides equity finance for SMEs.

So, where does Youth Employment Authority (Y.E.A) fit into all this? Does it meet the test of sound program design? First of all, the philosophy of markets and State, and their relative impact on macroeconomic outcomes such as employment, are markedly different. When the State creates jobs, it does so with a complex objectives matrix (social, economic and political).

In pursuit of a trade-off between economics and politics, States run large fiscal deficits, the financing of which create inflationary pressures and distort market operations (interest rate and investment allocations).

So training 500 youth under Y.E.A’s Prison Module, for instance, at a time when government is scaling back on public sector wages, may be part of the problem and not the solution. The second reason why Ghana’s current youth employment approach is ineffective is the structural context within which program activities are implemented.

Evaluability assessment reveals weaknesses in program logic, especially the link between assumptions and objectives. Training people to be employed assumes the availability of employment avenues.

But lack of employment avenues was the policy question that motivated the setting up of Y.E.A in the first place.

Finally, program performance assessment seems to focus largely on outputs instead of outcomes and impact.

For instance, there is evidence to suggest that value-for-money assessments were not factored into Service Level Agreements (under GYEEDA) with private sector partners. It remains to be seen if Y.E.A under Act 887 is anything more than change of name.

What about Youth Enterprise Support (Y.E.S), does it meet the essential criteria of sustainable policy? Y.E.S is an interesting model that meets two (potentially) of the four policy design criteria.

But unlike other investment schemes, the risk of moral hazard and adverse selection is unique to Y.E.S by virtue of its program design, a situation which increases probability of default by clients.

Other potential risks are political interference, portfolio structuring (more debt than equity investments) and limited exit channels for investment liquidation.

The ultimate test of program success is self-sustainability. Therefore any policy whose success depend on government for continuous funding, is an inefficient policy tool for pursuing low unemployment. Youth Enterprise Support, like Venture Capital Trust Fund, could be a promising program for a private sector led approach to job creation, if sufficient attention is paid to program design.

Aligning entrepreneurship, job creation and economic growth

Ghana’s youth development agenda must be grounded on four key pillars in order to ensure sustainable growth;

1. Youth Skills Development – The youth (15-35yrs) constitute about 19% of Ghana’s working population. Unfortunately quite an awful lot are jobless, posing a threat social security. Skills programs must focus on developing problem-solving and entrepreneurial skills in order to build a critical mass of viable start-ups.

2. Organizational Coordination – National Youth Authority (NYA) and Youth Employment Agency (YEA) appear to have overlapping interest, which is skills development. Government must consolidate them in order to make fiscal savings.

3. Emphasis on Agriculture and Agro-processing – The slow growth in agriculture and the need to reduce food import bill present opportunities for agro entrepreneurship. Youth policy and programs must focus more on agriculture and integrate forward into agro-processing.

4. Capital Market Integration – Youth Enterprise Support must make more equity than debt investments in start-ups. This would ease Cashflow pressure on start-ups and also increase feasibility of investment exit through the Ghana Alternative Exchange market.

–

By: Rural Heights Foundation [www.ruralheights.org]