The chief executive of a company that created highly-secure smartphones allegedly used by some of the world’s most notorious criminals has been indicted.

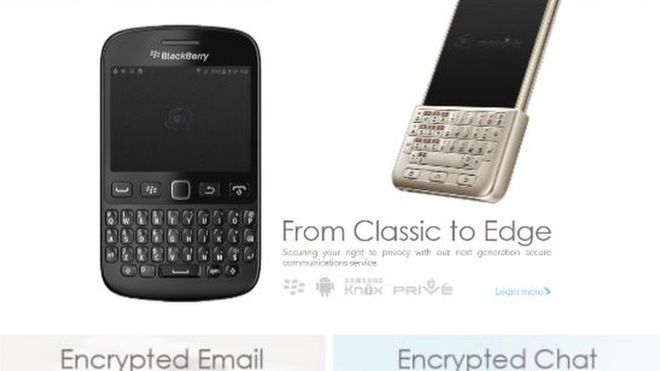

Canadian-based Phantom Secure made “tens of millions of dollars” selling the modified Blackberry devices for use by the likes of the Sinaloa Cartel, investigators said.

The charges marked the first time US authorities have targeted a company for knowingly making encrypted technology for criminals.

The Department of Justice arrested Vincent Ramos in Seattle last week. He was indicted on Thursday along with four associates.

The BBC has been unable to reach Phantom Secure.

They are charged with racketeering and conspiracy to aid the distribution of drugs. Both crimes have a maximum penalty of life in prison. Mr Ramos is the only one of the group currently in custody.

“This organisation Phantom Secure was designed to facilitate international drug trafficking all throughout the entire world,” US attorney Adam Braverman told the BBC.

“These traffickers, including members of the Sinaloa Cartel, would use these fully-encrypted devices to facilitate their drug trafficking activities in order to avoid law enforcement scrutiny.”

‘Handful of other organisations‘

Blackberry did not respond to requests for comment on Thursday – and investigators would not say whether the firm had worked with them on this case. Mr Braverman said Blackberry was not alone in having its handsets altered for illegal purposes.

“Our understanding is there are a handful of other organisations that exist like this. The FBI, and our office, will continue investigating not only Phantom Secure but any other company that provides this kind of communication device to criminal organisations.”

He added that while almost every smartphone on the market offers hard-to-crack encryption – as well as apps from Facebook, Google and Apple – Phantom Secure should be held culpable for what the users of its services were doing.

“The difference is this company was specifically-designed to aid international drug trafficking organisations,” he said.

“The only way that you’re able to actually utilize one of these devices and obtain one of these devices is if somebody else vouched for you.”

Phantom Secure sold devices on a subscription basis at a cost of $2,000-$3,000 for around six months of use.

In order to become a customer, an existing user must vouch for the new person. That system, authorities said, was a way of preventing law enforcement from getting hold of the devices.

Agents estimated as many as 20,000 Phantom Secure-modified handsets are in use around the world.

Communications through the phones are automatically routed to servers in Panama and Hong Kong, according to court documents, making data more difficult to trace.

Phantom Secure could also remove key functionality from the devices to lock them down, such as voice communication, microphone, GPS, camera, internet and messaging apps, leaving just the text functionality.

Law enforcement authorities have repeatedly been frustrated by encryption technology making it harder to access communications between suspects.

In 2016, Apple refused to provide a tool that would allow the FBI to unlock an iPhone belonging to Syed Farook, a man involved in a mass shooting that resulted in the death of 14 people.

On Thursday, a spokesman for the FBI reiterated the agency’s concern about criminals being able to “go dark” and hide behind these sophisticated technologies.

Privacy and open rights activists argue that removing or just weakening encryption would put everyone at risk of data theft and surveillance – not just criminals.